George Cunningham: Second World War in Broomhall ~ Part 2

The Signs of War

Researched and written by Gemma Clarke

The story below shows how the first alarm of the war brought panic to the street of Michael Road, which would have been the same for every other street in Sheffield as well as the rest of the country. Henry Pelling shows how in London when Chamberlain announced the outbreak of war on the radio and the London air raid sirens wailed out their warnings, the people of London were in complete panic. They were ‘half expecting immediate disaster from the sky, Londoners made their way hastily to the shelters, which were already prepared and assigned.”[1] The reaction across the country was full scale panic but the people of Michael Road, were not as advanced with their shelters and even with gas masks they were terrified.

The reason for why the people in the country were so terrified on this historic day with the outbreak of war could have been because of the interwar years in which there had been a lot of press on the radio, newspapers or Picture’s newsreels. These stories were all explaining what was going on in the world outside Broomhall, Sheffield. George throughout his stories showed how he grew up learning about Hitler and what was going on in the other countries, as well as the First World War and the legacy of that event.

For example the use of the word Great when referring to the Great War, shows how this event was remembered and how it was brought into the people’s consciousness. Robert Mackay shows that ‘IT WAS WISH fulfilment rather than realism that drove the phrase ‘a war to end wars’ into the public consciousness during the unprecedented slaughter of 1914-1918.”[2] George shows that he had, ‘read a lot about the Great War and seen All Quiet on the Western Front at the Star Picture Palace.’ He felt vaguely excited at the prospect of war. He states that, ‘after all, we always won and I imagined it to be a series of bayonet charges led always by a dashing young lieutenant in a smart uniform, brandishing his Service revolver, urging his gallant men on to certain victory.’

Evening: September 3rd 1939

‘The wireless news was all about the German advance and the heroic resistance of the Poles, some of whom were even making cavalry changes against the enemy tanks. Unusual for Dad, he didn’t go down to the Royal Oak, and then at ten o’clock he wound his watch, checked the blackout blinds, raked out the fire, covered the cage of Charlie the canary and we all went to bed. I was soon asleep, though my rest was disturbed by vivid dreams.’

Dreams turn into Reality

‘At one time I was with Moxay, charging at the Germans with a scaffold pole, and the next minute back at school, fighting with Jackie Wrathfull. He was shaking me, and with all my might I was trying to fend him off. The dreams turned into reality. It was Dad who had hold of me and was crying, ‘Come on, get up, the sirens are going!’

‘Indeed they were. I had heard them on practices, but then they only sounded the ‘all clear’ to make sure that people could hear them. This was the real thing – an uncanny moaning sound that would chill the blood in daytime, never mind dead of night. Bill and me scrambled out of bed. I started pulling my trousers over my pyjamas and got both feet down one leg; my braces were in a tangle and so was I. All I could think of was getting downstairs, which I did eventually.’

What next?

‘Down in the living room, Dad, Mam, Bill and me donned our gas masks with trembling fingers, then stood there looking at each other. We all looked alike: ugly. ‘What do we do now?’ None of us had any idea. We had no air raid shelter, Garlick’s cellar wasn’t ready, the Germans could soon be dropping bombs, gas and incendiaries on our defenceless heads, and all we could do was stand there and wait. Suddenly Dad had an idea. ‘We’ll go to Pickering’s. Ernest Garlick says they’ve got big deep cellars and that’s where he’s going if there’s a raid.’

Michael Road

‘We cautiously emerged into Michael Road. All was quiet and very dark in the blacked-out street, then there was a shuffling of feet and voices as people emerged from entries. At first the pace was slow, then someone broke into a trot. Everybody followed suit, even older people, until we arrived at the big wooden doors of the factory.’

Leader!

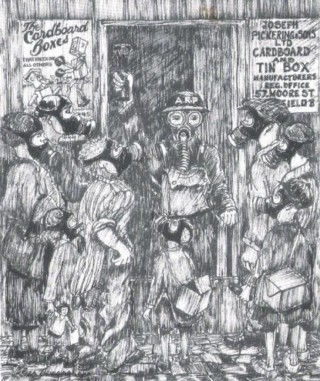

‘Mr Blackwell, Norman’s father, started banging on the small wicket gate with one hand, holding up his trousers with the other. There was a babble of voices, muffled by our gas masks, and more of the leaders began banging on the doors. Suddenly, there was a click, the rattle of a bolt, the wicket door opened inwards and standing there was the resolute figure of Mr Anthony, the caretaker of Pickering’s cardboard box factory. He wore a long dark blue overcoat and an ARP steel helmet, a military gas mask, and in one hand held a thick walking stick and in the other a large flash lamp. At the sight of him the babble ceased. Mr Blackwell and the rest stopped banging.’

The caretaker

‘Sounds emerged from behind Mr Anthony’s gas mask, then realising he couldn’t be heard he took it off, revealing a hot flushed face, stamped with authority and tinged with irritation. ‘What’s all the noise about?’ he demanded. Mr Blackwell tore off his gas mask to reply. ‘Cum on den, lerrus inter cellar, ‘e’ll be droppin’ ‘em soon.’ This request was backed up vociferously by the crowd, and for a moment it looked as though we would storm the gates and occupy the firm by force.’

‘Mr Anthony, though, was built of sterner stuff. He held up his torch like a mace bearer, and proclaimed, ‘I cannot allow anyone on these premises, night or day, without written authorisation from Mr Truelove.’ Albert Blackwell, maskless and toothless, looked at him with stunned disbelief. ‘Tha wot?’ he gasped. ‘Mester Truelove lives in Psalter Lane. Dusta think Jerries ar gunna wait ‘til sumdy runs up theer an’ back?’ Not to be moved, the guardian of the factory stood his ground and said, ‘It’s more than my job’s worth to let anybody in without a permit.’

Action

‘From the crowd angry rubbery mumblings became louder, then suddenly, from the back, a woman’s high-pitched voice screeched, ‘Shuv ‘im arter rooad, Albert, wisel all gerrus deeath o’ cowd standin’ art ‘ere!’ With the twin fears of death by bombing and pneumonia, there was a surge towards the gates. Mr Anthony tried to close the wicket gate, but Albert had his foot in it. For a long desperate moment, it looked as if the custodian would be overcome, then all at once a blessed sound rent the air.’

Relief

‘No heavenly trumpet ever sounded sweeter than did that first all clear of the war. On and on it went, but it could never be monotonous because it meant safety and freedom from fear, at least for the time being. As the last note faded away, sighs of relief and one or two ‘hurrays’ broke the silence, followed by a babble of conversation and the crying of children as we all took off our gas masks.’

Afterwards

‘Mr Anthony said farewell by banging and bolting the wicket gate, confident that he had done his duty. Back along Michael Road we straggled. I thought how different people looked from the day before. None of the men had collars and ties on; Albert Blackwell’s shirt lap was hanging out; all the women’s hair was untidy and quite a few hadn’t had time to put in their false teeth. At each entry people wished each other good night, a little self-consciously.’

The Blackwell’s

‘Our family lingered for a minute at Blackwell’s entry. Mr Blackwell had regained his composure and his appearance, having finally untangled his braces and put in his false teeth which he produced from his pocket remarking, ‘Ar purrem in theer in case ar got mi ‘eead blown off. Arve ony just gorrem an ar din’t want to gerrem brocken.’

‘He was quite a small man, though in my eyes his stature had increased considerably by his determined assault on the factory door. ‘Warra weekend,’ he expostulated, ‘Wot wi Wednesday gerrin’ licked yesterday at ‘ooam bi Plymouth, ‘n Jerries keepin’ us up hafe art neet, ar’ll be glad ter get back t’ work.’ From the darkness of the entry he said, ‘G’night, Sid,’ which to me was an unaccustomed familiarity because he had always addressed my father as ‘Mr Cunningham’.

Home at last

‘I was glad to get back to the peacefulness of our house, climb into the still warm bed and lay there, while thinking what an eventful fifteenth birthday I’d had, and wondering how many more I would live to see.’

PP. 57-60, Chapter 12, More George! (courtesy of The Hallamshire Press Limited).

[1] Henry. Pelling, Britain and the Second World War (Great Britain, 1970), P. 12.

[2] Robert. Mackay, Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain during the Second World War (Manchester, 2002), P.17.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page