George Cunningham: Childhood Memories ~ Part 3

Albert Moxay

Researched and written by Gemma Clarke

Making friends with Albert Moxay created for George an interesting business partnership!

Albert Moxay

‘As my schooldays progressed I widened my circle of friends. One such was Albert Moxay, who lived in one of the old back-to-back houses near the school. He had a little round face with a turned-up nose which defied the laws of gravity by continually running, and his red hair, when cut in the fashionable penny-all-off style, made his head an irresistible target for open-handed slaps from his larger friends. His mode of dress was casual and in keeping with the times. It altered little, be it Winter or Summer, consisting of a maroon jersey with a large hole in the front and baggy tweed short trousers with a hole in the back, from which poked, as the finishing touch, a few inches of shirt lap.’

‘Stockings he dispensed with and a pair of boots, supplied by the Lord Mayor’s Appeal, quickly found their way to the pop shop, so his range of footwear was apt to be somewhat varied, ranging from worn out plimsolls to football boots with no studs. On one occasion, I caught him up on the way to school and noticed that the usual spring was missing from his step. He was hobbling due to the fact that he was wearing women’s shoes with the heels sawn off. Albert’s appearance was made even more interesting by well-defined tidemarks round his neck and wrists which were best seen to their full advantage after his weekly ablution and earned him the nickname Mucky.’

Bugs!

‘Even with all these attributes he wasn’t a snob and I was flattered and even a little touched when he once offered me a bite of carrot. I suppose our friendship really got on to a steady footing from the time I met him coming along Moore Street, carrying a large parcel. He answered my enquiry as to the contents with the laconic reply: “Distemper, we got bugs.”

“Bugs!” I gasped. “Wow!”

Encouraged by my interest he pulled up a threadbare sleeve and proudly showed me dozens of little red marks, clearly discernible even through the grime. “Ah’ve gorrem all o’er mi,” he remarked, with an air of complacent proprietorship, at the same time glancing somewhat disdainfully at my unmarked knees.

“When it’s warm like dis,” he continued, “dey wait ’til you’ve gorrin ter bed, den thi cum aht from behind wallpaper ‘n set abaht yer. Mi Mam sez they must ‘a’ cum from next door ‘cos thi ‘ad louse van other day which gassed ’em aht ‘n sent ’em to us.”

By this time we had rounded the corner into Young Street, and Mucky, warming to his theme, kept digging me in the side with his elbow to emphasise the point. “Sumdy telled ‘er if we caught biggest bug ‘n painted ‘im blue it’d freeten all others away – ‘n mi Dad did do, but next neet thi wor twice as menny. Mi Dad sez thi must orl bi bleedin’ Wensdyites! Enny rooad up, wot e’s gunna do nar,” continued Albert, pausing only to wipe his nose with the back of a ragged sleeve, “is tear orl paper off, den paint walls wi’ this ‘err red distemper so if thi is a few knocking abaht at neet ‘n we squash ’em it waint show up on wall.”

The Moxay Residence

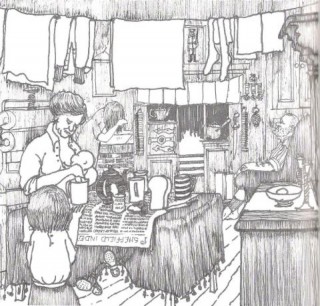

‘I hesitated as we reached the door of the Moxay residence but Mucky, with the casual air of a born host, walked in first, saying over his shoulder, “Cum in, it’ll be orl reight.” I followed him, at least as far as I could because there was a big sideboard just inside the door which took up most of that side of the room. Albert’s mother sat at the table which was covered with a sheet of the Sheffield Independent performing the dual role of a tablecloth and an opportunity to catch up with yesterday’s news.’

‘On it was a brown teapot with a chipped spout, several pint pots, a stone dripping jar, half a loaf of bread and a knife with no handle. A tin of condensed milk with the lid stuck up in the air and a blue paper bag of sugar completed the informal breakfast table. In one arm she cradled the youngest Moxay, who was enjoying his morning repast at the maternal source of nourishment, whilst with the other hand she dipped into her tea a dripping-ed crust which she thrust into the mouth of his sister.’

‘Two lines of washing hung across the room, which was comfortably furnished with a black horsehair sofa, propped up at one corner by a pile of bricks, two matching armchairs and a mangle. As the floor space was somewhat limited, two of Moxay’s younger brothers were under the table engaged in a wrestling match refereed by an occasional well-directed kick from mother.’

Molly Moxay

‘In a corner of the room at the side of the copper was a low stone sink where Molly, the eldest child of the dynasty was completing her toilet with a fine-tooth comb and a sheet of paper. She flung back her mop of red hair, shook the paper into the fire, then quickly turned and smiled at me with a quiet charm, displaying an alluring width of pink gum, flanked by two pointed eye teeth. Unaccustomed as I was to female company I shifted self-consciously from one foot to the other, feeling my face going red and was relieved when Mr Moxay levered himself up from an armchair and inquired of Albert, “As ta got mi suit, son?”

Mr Moxay

‘Mr Moxay was stockily built with close cropped red hair and not having shaved for a few days it was rather difficult to determine where his face ended and his head began. His forearms were covered with tattoos and I noticed, as he lit a cigarette, that on the fingers of one hand were the numbers 1914 and on the other, 1918. He was clad in a long flannel shirt with a brass stud in the collar and woollen combinations which served him as both undergarments and sleeping attire.’

‘The prodigal cleared a space on the table and unwrapped his parcel to produce a paper bag of distemper from Eager’s and a navy blue suit with a pawnbroker’s ticket pinned to it. Moxay senior inspected the little yellow card and stuck it behind the mirror over the mantelpiece, then climbed into his trousers and put on the jacket, standing and turning round in front of the fire to smooth out the creases, at the same time whistling a few bars of Tipperary.’

The War Warrior

“Mi Dad wor in Gret Waar,” said Albert gazing in admiration at his noble sire. “‘E wor o’er yonder wi ‘Allamshers fer fower year.” And indeed all round the room were the warrior’s trophies and spoils of war. In the hearth were two brightly polished brass shell cases and a German helmet filled with coal. At the side of the fireplace hung a belt of bullets and alongside those a long bayonet which came in useful for chopping sticks, toasting bread or poking the fire. I knew what all these were from pictures in the War Illustrated which we had at home and I gazed with interest at a photograph on the wall showing Mr Moxay in uniform with a rifle slung over his shoulder.’

‘Underneath it, hung on nails, were a cap badge, a row of medals and a Mills bomb. “Ah can play wi it, mi Dad sez it’s orl reight s’long as ah doan’t pull this ‘ere ring,” Mucky informed me, tossing it up and down. “Cum on, ah’ve got sum coil ter fetch.” I declined his mother’s offer of a slice of bread and dripping and we left the house followed by Molly, who as I looked back was standing on the doorstep, smiling bewitchingly and picking her nose.’

Fetching the Coal

‘I was fairly experienced in fetching coal for like most people in the neighbourhood we couldn’t afford to buy a load, so once a week Mam sent me for a barrowful. Albert fetched coal for his household for which he received nothing and for owd lady Dyson who gave him a penny and a slice of seed cake. She was waiting at her door for us, a stout old lady dressed in a black blouse with silver buttons and a long black skirt which was so voluminous that it concealed the two sticks she used for support.’

“She’s got Artheritis,” whispered Mucky. “Sum times it’s that bad, she falls darn.” The matriarch stooped to hand over the coal money and I caught a whiff of an aroma similar to the ones I had smelled at pub doors. “Missis next dooor wants a quarter, Albert luv, will y’ fetch her one?” Mucky assented and off we set after being warned, “See ‘e dunt purreny shale in it, last lot wor banging rahnd kitchen that bad ah ‘ad ter put oven dooor across fire or itada brocken orl winders.”

“Tell thi wot,” exclaimed Albert. “We’ll gu to coilyard at top o’ rooad so it’s orl darn ‘ill when barrer’s ‘evvy ‘n it’ll bi easy gooing back wi empty un.”

We entered an archway which led into a yard behind a row of houses. Mucky went over to a row of barrows which were leant up against a wall and pulled out one of the smaller ones. “That’s abart best ora bad lot,” he remarked, handing it over to me after testing the shuttle and wheels. He chose a larger size for himself, adding “Owd ‘Ackitt’s barrers aren’t much cop, burris coil’s orl reight.”

Henry Hackett Coal

‘One of the house doors to which a board was nailed bore the inscription Henry Hackett Coal Dealer. It opened and a man emerged carrying a parrot on his arm. Its brilliant blue and gold plumage glowed like a huge jewel against the blackness and grime of the coalyard; it stretched and flapped its wings as if yearning to escape and fly away to some green and leafy jungle. Mr Hackett placed it carefully on a perch near the window, picked up a shovel and started filling a big iron scoop on one side of the scales. He was a tall, thin man with merry blue eyes; at least one of them was, but the other seemed to stare rather fixedly as I watched him adjust the weights. “It’s a glass ‘un,” Albert informed me later. “‘E’ad ‘is own shot art in Waar.”

“Quarter hundred weight, just,” said the coal dealer, tipping the cobbles into my barrow. Albert’s was filled in like manner and he paid Mr Hackett who waved aside the sixpence deposit on each barrow, saying he knew Mr Moxay and that he would give us some spice if we returned them straight away.’

The Race!

‘I picked up the shafts and we rumbled out of the dark yard through the archway into the daylight of the street, picking up speed as the incline seemed to render our loads weightless. Every few yards we would put the brakes on by slaring out feet, then set off again in another mad rush down the cobbles. I was just behind Albert, but going well and in an attempt to overtake him my wheel hit the causey edge and flew off as the cotter-pin snapped and with a sickening lurch the barrow tipped on its side and shed its contents. Mucky slid to a standstill, howling with laughter at my misfortune, but ever resourceful he rummaged in his trousers pockets and from a tangled mass of string, cigarette cards, marbles and a lump of bubbly gum covered in fluff he produced a large rusty nail with which he effected a speedy repair.’

Destination and Rewards!

‘We arrived with no further mishap at our destination to find ‘Owd Lady Dyson’ and her next door neighbour, Mrs Gurstang, waiting for us. “Fill mi this bucket, luv, and put rest darn grate,” she told me, pulling the black shawl she always wore a little closer round her shoulders in anticipation of the warmth to come. My reward from her for these labours was a piece of spice loaf and a ha’penny and as Albert and I trundled our empty barrows up the street, munching contentedly away.’

Added Rewards!

‘He made life appear even rosier by reminding me that Mr Hackett would give us some spice in appreciation for the safe return of his vehicles. In fact he gave us a double allowance because Mucky almost filled his barrow with manure kindly deposited in our path by two railway dray horses. “Owd ‘Enery’ll like this,” chortled Albert, scooping up the steaming globules with the side of his foot and the barrow shuttle as a make shift shovel, “‘E puts it on ‘is rhubarb and ‘e dun’t get much sin ‘is ‘orse dropped deead.”

PP. 35-39, Chapter 11, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

The End of the Holidays!

‘The days, of which at first there seemed to be an endless supply, now started slipping away at an alarming rate, no matter how hard I tried to hoard them. Vainly I tried to stem the tide of approaching school by pretending that it was the first week of the holiday instead of the last. Then one morning I opened my eyes and knew it was Black Monday because Mam was calling me from downstairs, something she hadn’t had to do for a month. It wasn’t so bad after all to be back at school and to resume my scholastic career with fellow pupils, some of whom I had almost forgotten.’

George’s Interests

‘I had also developed an interest for reading and in the cupboard below the one where Mam kept the pots was my library. At least the top shelf was because the bottom one was full of boots and shoes and the hobbing foot. I had a selection of comics, usually the Funny Wonder and Butterfly and my special favourite, Chips. I always started at the back page with the capers in Casey’s Court and then followed Weary Willy and Tired Tim in their endless adventures on the open road.’

‘Sometimes I swapped two comics with Vinny for a copy of Film Fun which was a bit out of my price range. The pride of place was taken by a much thumbed annual of Tom Webster’s cartoons from the Daily Mail. I financed my excursions into the fascinating world of literature with the ha’pennies earned by running errands, fetching coal and helping Albert in his fertilizer business. This was very lucrative as quite a lot of people had a little patch pf earth bounded by a few bricks in their backyard and optimistically called a garden.’

The Fertilizer Business!

‘Mucky’s tools of the trade were an iron bucket borrowed from a window cleaner when he was up the ladder, and a small wooden Gossage’s soap box. We had no earth to plough or seed to sow but our crop was always plentiful and waiting to be gathered. I quickly learned Albert’s technique of using a piece of cardboard and the side of my boot to shovel up Nature’s bounty of delectable dung.’

‘The only snag from my point of view was that as junior partner I had to carry the box which when filled and heavy was directly under my nose, whilst Mucky could swing his bucket happily at his side. The going rate was a penny a load and he had built up a round of regular customers to the extent that my share of the profit could be as much as twopence. This added wealth meant that I could indulge further in my passion for reading and two or three mornings a week before school I walked down to the newspaper shop in Clarence Street.’

P. 56, Chapter 18, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

No Comments

Add a comment about this page