George Cunningham: School Life ~ Part 1

St Silas School

Researched and written by Gemma Clarke

George Cunningham went to St Silas School on Hodgson Street, Broomhall, until the age of 14 when he had to leave to find work.

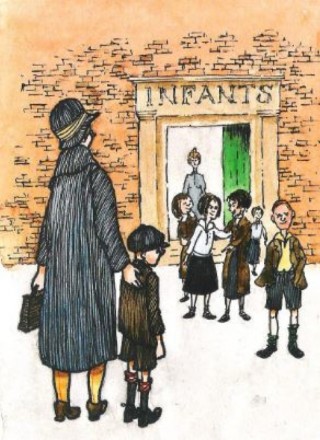

‘The Infants Department was in Hodgson Street and we went through an iron gate into the yard and I stood close to Mam, watching the milling mass of my future school mates. Some of the lads I knew, but they had all the superiority of a few weeks’ schooling and pretended not to see me.’

‘Most of the girls stood in groups and I saw one point at me and whisper something which made the others giggle. “If she calls me Georgie Porgie I’ll bash her,” I vowed, glaring under the neb of my oversize cap.’

Mrs Pollard

‘A lady came towards us. She was tall and grey-haired with a dignified manner which relaxed into a smile as she said in a quiet voice which was yet plainly audible over the noisy rabble: “I am Miss Pollard, the headmistress. What do they call you?” Mam pulled off my cap and red-faced I gulped in reply, “Georgie,” which set the girls giggling again.’

‘One look and a raised finger from the head silenced them immediately as she took my hand and led me into the school. I looked over my shoulder as we went through the door and saw my mother standing outside the railings. She waved a hanky at me, then put it to her eyes as she hurried away along the street. During the next two years I learnt to read and write, which I liked, and to do simple arithmetic which I found very difficult.’

P. 11, Chapter 2, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

School Days

‘The days seemed very long at first and I used to spend the playtimes gazing through the railings or watching the weather-vane high up on the wall of the girls’ school. I thought it had something to do with us down in the yard: on calm days it would be motionless and the groups of children would be fairly orderly, then a gust of wind would whirl round in a cloud of dust, blowing hair, skirts and caps about in wild abandon as the vane spun round, as if winding up a lot of clockwork toys.’

George’s Friends

‘Gradually I settled into the routine of school and going home at dinner-time, usually with Vincent Crookes and Norman Blackwell, who both lived in the yard next to mine. Vinny had straight, very fine fair hair which fell over his forehead. One of his front teeth was rather prominent and he had the habit of sucking air past it when he got excited.’

‘Norman was curly-headed and dark, with an inclination to plumpness, helped by a fondness for bananas which resulted in his sometimes being referred to by the nickname of ‘Nana’s’. I was tall for my age, or so my mother told me, with arms like pipe cleaners and legs so thin that my long woollen stockings were always slipping down round my boot-tops, until eventually she made me some black elastic garters.’

P. 12, Chapter 2, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

Interview with George

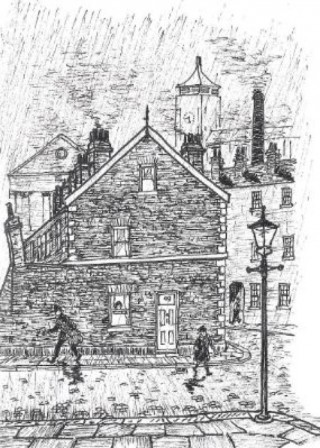

George Cunningham was stood outside St Silas School, in the school yard when being interviewed and he was talking about his life at St Silas School.

George was asked what the name of the school was and he said, ‘St Silas, St Silas School, we used to call it St Silas Academy for young gentlemen, Headford St.’

‘Infant School, when I started when I were five year old and everybody went here, came through this gateway and we went here from 5 to about 7, then we went up to Lads. This is girl’s school here, went round the front, to the Big Lads as they call it, then 7 year old and from 7 till 14 I was in that school round there.’

‘This is where I started school, 7 years old in what 1931, what they call the Big Lads, Mr Barlow head teacher budding fine man.’

‘This was our playground many a game of football, cricket what have you.’

‘No school meals then and this school probably had what 130 lads, no girls, the girls were round there and there was a water tap which was in lobby come hall here, one corpstove, in the middle of the big room and that was the only heating. The sanitary facilities as you call them were in that corner over there, urinals and WC’s and this is where we spent our learning years.’

‘Now the School uniform as such was err a cap and I mean if you had a cap a new cap the first thing that anybody, the bully, the school cock as you call him. He’d grab it off you, bite the button off and tore the cap over the wall so you followed your cap and the rest of it was a jersey with a woollen tie, usually with a hole worn here, [He was showing that the hole was in the front of the jersey] everybody had a hole in their front, and sleeves down here, and you got a hankerchief. Short trousers winter and summer, no long trousers you weren’t put into long trousers until you were 14, that is what they call you a bridge then, I’m taking him to be a bridge somebody used to say, and buy a pair of long trousers but you were 13 or 14 then. Boots, no-body wore boots, no-body wore shoes, plenty of studs in them, they had to last you out for years and years and then they were passed down when they got too small for you, or you too big for them, and err this is why we used to play football, cricket up at that top end, there we used to chalk some stumps up there, and there’d be in 130 kids in this playground, milling round. The gate was kept locked usually one teacher who kept an eye on us breaking fights up and what have you.’

Mr Roy Newman, George Cunningham’s Life, Paintings and Interests, Dinnington & District Historical Society, www.dinningtonhistory.co.uk/products, Reference copy available at Sheffield Local Studies Library.

Inside St Silas School!

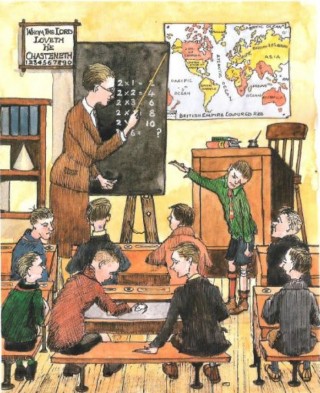

‘We stood in a small stone-flagged lobby with rows of iron coat hooks and a sink with a cold water tap in the corner. There was a lot of shoving and coughing, with our breaths steaming until the door opened and we shuffled into the Big Room. The older lads of Standard Eight, some of them already breeched, stood at the back surveying the new intake of runts. In the middle of the plank floor, at the side of a big cast iron Tortoise stove, was the raised platform and desk of Mr Barwell, the headmaster.’

Mr Barwell

‘In his early forties and a veteran of the Great War, he stood erect, though a little portly and grey haired, as he surveyed his flock. We droned through the Lord’s Prayer, then Mr Barwell read a passage from the Bible. He spoke in a quiet voice which somehow seemed directed at each one of us and every time my attention wandered, his eyes, piercing and dark behind horn-rimmed glasses, compelled me to look up at him. His staff stood at strategic positions around the room, alert for any signs of yawning, nose picking, or surreptitious ankle tapping.’

Mr Beresford

‘Next in command was Mr Beresford, who had the whitest teeth I have ever seen and the brightest polished black shoes and smartest razor-creased trousers, this side of Burton’s window. Out of his hearing, I heard him referred to as ‘Owd Pew’, a nickname he acquired when he read an extract from Treasure Island about the blind beggar of that name and the next day, due to some eye inflammation, he arrived at school wearing a black eye-patch. Winter or summer, he wore a trilby hat and carried a raincoat over his shoulder. The mere sight of his upright figure, erect and shining clean, as he marched up Young Street was enough to quell the shin-kicking spitting and gutter-rolling outside the school gate.’

Mr Thomas

‘Mr Thomas, square-jawed and stocky, known as ‘Dicky’, was reputed to have played rugby for Wales; he stood next to his compatriot, Mr Averill.’

Mr Averill

‘Mr Averill, who was young, tall and elegant in a grey suit and white collar and altogether too much of a scholar to be a teacher at the St Silas Academy for the sons of gentlemen.’

Mrs Manion

‘Mrs Manion stood a little to one side and nearest to the stove as a concession to her position as the only female in the school. Morning prayers over I marched into Standard One which was presided over by this good lady. She was little over medium height, with neat brown hair and wore a neat brown cardigan, a neat brown skirt and the neatest brown, polished, laced-up shoes. Everything about her and around her was neat: the papers, books and blotter on her desk were arranged just so. And she even contrived to bring some neatness into us.’

Our Teacher

‘We were seated in pairs at wooden desks with ink-wells and steel-nibbed pens, a big improvement on the chalk and slates of the infants school, or so I thought until I was stung by an ink pellet on the back of my neck. Reaction from Mrs Manion, although she was writing on the blackboard, with her back to the class, was instantaneous. “Wharton!” she commanded, and out shambled the miscreant. How could she be so sure, I wondered, bewildered, as he held out a guilty ink-stained paw to receive a neat whistling cut from a neat thin cane. I settled steadily into the routine of the Big Lads’ school, feeling quite superior to what we called ‘littl’uns’ over the wall.’

PP. 14-16, Chapter 3, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

Christmas School Treat

‘Then one foggy night with yellow-green haloes round the gas lamps I walked along Moore Street and into the school yard. It was crowded with my fellow pupils, but for once there was none of the usual scuffling and tugging; this was because each of us carried a cup, saucer and plate in readiness for the Christmas school treat.’

Amazement!

‘At last the door opened and we filed in fairly decent order into the Big Room. I gazed in wonderment at the transformation which had taken place since the afternoon. Festoons of paper chains hung from the walls and ceiling; branches of holly, white with snow, blazed with red berries and all along the bottoms of the window frames frost sparkled and glittered. The desks had been covered in clean white lining paper and Mr Barwell’s was graced by a big red candle – which had to be moved to one side because of the heat from the stove.’

The Meal

‘No teachers were present but at first I felt a touch of guilt when I put on a paper cap. This soon faded as the clean pinafored ladies of the parish filled my cup with hot sweet tea and brought round trays full of potted meat sandwiches and thick slices of bread and dripping. None of us had eaten since dinnertime in preparation for the feast and the luscious viands quickly vanished under out onslaught. “You can have as much bread and dripping as you like,” beamed Mrs Throppleton, who lived not far from us but was regarded as somewhat superior because her husband was a manager at Wostenholm’s and wore a stiff wing collar and bowler hat.’

Tasty!

‘Down went the thickly plastered slices, helped on their way by scalding tea and, licking greasy, salted lips, we were regaled with hot sausage rolls, followed by mince pies. Surely the world could have no more to offer I thought, as I put my hand under my jersey to loosen a waistcoat button. Yet it had: our cups were rinsed and filled with delicious fizzy foaming lemonade. Then Miss Alflat, who sometimes played the organ in church, sat down at the piano and in a very sweet, thin, trembling voice led us in carols. Good King Wenceslas was my favourite and as page and monarch trudged through the snow even Jimmy Wrathfull looked friendly as he bellowed his way to St Stephen’s fountain, his jacket pockets full of purloined mince pies.’

P. 26, Chapter 7, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

Winter

‘In the classroom, heated by an iron coke stove which only warmed the favoured few near to it, I breathed on my cupped hands and then sat on the one I wasn’t using, after pulling my stockings as far as I could over bony shivering knees. One morning when we arrived, the inkwells were frozen solid and had to be thawed-out on the stove. Harry Flathers’ long nose dripped like a tap and I always knew when he was copying by the nearness of his sniffs.’

P. 72, Chapter 26, By George! (courtesy of Paul Hibbert-Greaves/Hibbert Brothers).

No Comments

Add a comment about this page