George Cunningham: Working Life ~ Part 3

Harry Benton

Researched and written by Gemma Clarke

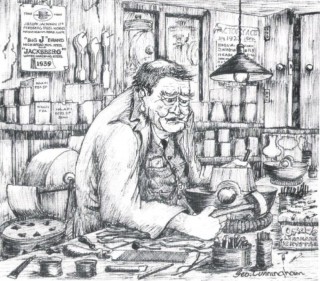

When working at Viner’s, George met one particular character called Harry Benton who taught him the skills of die-sinking.

Harry Benton

‘My first impression, too, of Harry Benton was favourable. He was seated at the bench with a hammer in one hand and a chisel in the other, his entire body shaking in a paroxysm of silent coughing. The timekeeper grimaced in compassion and left me for my interview to begin. Gradually the eruption faded away, the heaving shudders quietened down, then finally, with a tremendous cough, Harry cleared his throat into a piece of paper, which he chucked into the waste bin. ‘That’s better!’ he gasped, wiping his eyes with a red-spotted handkerchief, then lighting a cigarette.’

‘Dad had said that my prospective gaffer’s age was sixty-four, but viewed from the superiority of my callow sixteen years he looked like Methuselah. Heavily-built, and a little stooped, his face was deeply lined and bedecked with bushy grey eyebrows, from under which twinkled a pair of rheumy, blood-shot, but humorous brown eyes. What hair he had was short but thick, except for a large bald patch on top of his head, which seemed to have been plucked bare to supply tufts for his ears, nostrils and cheekbones.’

‘He wore heavy Derby tweed trousers and a waistcoat of the same material, liberally powdered with ash, because he never buttoned his brown smock. His footwear – black leather boots cobbled with tremendously thick soles and heels – gave him an extra few inches in height, but, which he later confided in me, he had worn since he was a lad on account of having weak ankles and the extra weight might strengthen them.’

George’s Job

‘I stood at the side of him while he outlined my duties. He said, ‘You’ll work for me. I’ll pay you an’ stamp y’ cards, y’ll not ‘av t’ clock in ‘n y’ll not need a pass to go out.’ I thought this was great. Harry explained further. ‘Viner’s, when they had this factory built a few years ago, took in a lot o’ the outworkers who used t’ do work forrem, ‘n let ’em have workshops rent free, n’ each gaffer pays his own lot ‘n keeps what’s left for hissen.’

‘I was a bit disappointed when he told me that we worked Saturday mornings, because Viner’s was known for working a five-day week, the only firm doing so in the cutlery industry. Still, there was a war on. Later I was told the reason for turning in on Saturday was so that Harry, an inveterate backer of horses, could escape from his wife’s surveillance to have a bet.’

First Day in the New Job

‘On my first morning I arrived early, opened up the shop, swept it out and lit the gas ring. Harry duly arrived, put down the old leather bowling bag in which he carried his dinner and the Daily Herald, took off his trilby and jacket and donned a soiled brown smock. On his bench, chisels, punches and files of every description, from small rifflers to large bastards, lay in great profusion. ‘Watch me for a bit, it’ll give y’ some idea,’ he told me, lighting a cigarette. In front of him was an oblong tin box that had once contained ‘Oxade’ lemonade crystals. This was a resting place for Harry’s cigarettes which, while I watched him work, burnt themselves out, leaving a little caterpillar of ash. At each blow of a hammer, this floated in the air like a miniature snowstorm, making Harry cough and sneeze.’

Smoking or Die-sinking

‘After a while, during which he had two fags on the go at the same time, one on the box and the other in his mouth, and I was beginning to wonder whether I had come to learn smoking as well as die-sinking, he took me to the end of the bench, where stood a huge round cast-iron die which was indented with the impression of a fire watcher’s tin hat. This had to be scraped, riffled and stoned with carborundum sticks and finally polished to a very high standard with a mixture of oil and powdered emery. For all my first morning as an apprentice die-sinker, I rubbed away, seemingly making very little progress, but Harry seemed satisfied when inbetween bouts of hammering and coughing he came over to me.’

An Extra Role!

‘Every few minutes the door opened and a workman walked in, had a word or two with Harry, a look at the back page of the Daily Herald, then left a slip of paper and some money on the bench. Just before dinner, Harry called me over to him. Handing me a bundle of papers and coins, he said, ‘Come wi’ me.’ Off we went through the press shop. A lot of girls were working on machines and fly presses, and as I passed some of them whistled. At the time house, Bert Denham let us out on to the pavement.’

Meeting Somebody New

‘Nah then, George,’ quoth Harry, pointing along Bath Street, ‘See that chap in a raincoat, standin’ at bottom of an entry?’ I nodded. ‘Right, just nip along an quick as y’ can, gie ‘im them slips ‘n money an’ don’t let anybody see yer.’ Off I went. As I approached my quarry, two men on opposite corners of Headford Street eyed me suspiciously, but seemingly satisfied they relaxed and resumed their loitering. I handed over my cargo, which was adroitly stuffed into the bulging pockets of the raincoat man. He was a man of medium build, sharp- featured with more colour in his cheeks than most people I knew. ‘Thanks son. Ar ta Harry Benton’s new lad?’ was all that he said. It dawned on me that he was a street bookie, or at least stood for one, and he seemed quite a nice chap.’

Thomas Street

‘Every day, sometimes two or three times when there was a lot of meetings, I delivered betting slips and money. If there was anything to draw I went along to a little back-to-back house in Thomas Street, and, without knocking, entered into the abode of Mr Harrison. No matter what the weather was like outside, a bright coal fire glowed in the grate of a black-leaded Yorkshire range. Ornaments, pictures and highly-polished heavy furniture blended with the mouthwatering aroma of freshly-baked bread cakes to create a peaceful little haven, especially in winter. In the middle of the room stood a big scrubbed table without a cloth, but covered instead with betting slips, piles of coins and even bank-notes.’

Losing was Good!

‘Mrs Harrison, neat and tidy as her house, and always with her hair neatly coiffured, could reckon up the most complicated bet in a few seconds and knew to a penny how much to pay out. She was always smiling, even when paying out a large sum of money, and sometimes, when the amount was small, she handed me half a still-warm-from-the-oven bread cake, liberally spread with dripping. I enjoyed this treat, and looked forward to a day when there was little to draw, although Harry Benton and the rest of Viner’s punters didn’t.’

PP. 72-75, Chapter 15, More George! (courtesy of The Hallamshire Press Limited).

Harry Benton

‘My career as a die-sinker was, to say the least, a trifle disorganised. Harry Benton, now in his late sixties, was a sick man. Some days he did more coughing and expectorating than die-sinking, although his good humour never flagged. The periods he had to stay away from work varied from odd days to weeks at a time, so when this happened I was in charge of the die shop and the betting slips. Born in 1876, Harry was one of the old school of Victorian craftsmen who had never moved with the times. All the machining and surface grinding of the steel blocks was done at James Bros, a small engineering firm in Trafalgar Street.’

George’s System

‘I soon evolved quite a good system on Harry’s off days. The first two or three hours of the morning were employed in working on a die until the betting slips started to come in. ‘Mac’ Coles was an invaluable assistant and advisor to me, especially on big race days. He was a spoon and fork stamper, and so expert at his job that he invariably had a copy of the Daily Herald opened at the racing pages beside him on his drop stamp. The hammer was operated by a foot pedal, and Mac could pick out his horses and decide on what bets to have whilst still stamping, never once making a waster.’

Derby Day

‘On Derby day I put all the slips and money into a paper bag, picked up two heavy blocks of steel due for machining and set off along Bath Street. It was a beautiful sunny morning and, in spite of the weighty dies, I was glad to escape from the factory. As evidence of the race’s importance, a little queue of old men and one or two women had gathered up to Fred Harrison, each of them wanting to make sure that their money was on. I stood at the end of the line, enjoying the sunshine and good-humoured remarks.’

A Situation!

‘A stout woman, whom I knew as Mrs Giddings, robed in a coverall, a sacking apron and plimsolls, had just said impatiently, ‘Cum on, shek thissen, ar’ve got mar mester’s dinner t’purron,’ when suddenly, without warning, Fred, who always had on eye for the money and the other for his touts, turned abruptly and shot up the entry. Everyone except me seemed to know just what to do. The men, old though they were, hobbled at a fair lick after the fleeing bookie, and the women disappeared quickly into nearby houses, leaving me, weighted down as I was, alone in the deserted street. There I stood, gawping, wondering what was happening, when behind me a door opened and a firm hand clutched my arm and dragged me inside a house.’

What’s going on?

‘The door was quickly slammed behind me and a rough voice growled, ‘Wot wor tha standin’ theer for like souse? Dusta tha wanta t’ get pinched?’ The closed curtains in the little front room made it dark and hazardous for me after the brightness outside, and all I could do was obey my rescuer when he ordered, Put them dies on’ flooer an’ cum wi’ me.’ I did as I was told and stumbled after him, bumping into furniture, then through a door in a living room.’

A Strange Meal!

‘Around a large scrubbed table, industriously plying knives and forks with every sign of enjoying a cooked dinner, were seated a man and a woman, also without hat and coat. The man was Fred Harrison. Before I had the chance to ask him what he was doing, the woman quickly fetched two plates from a cupboard, and just as quickly filled them with steaming hash from a large stewpot. My host plonked me down in a chair beside him, and I mechanically started to eat. None of the people seemed a bit surprised at my sudden appearance at the table, but carried on eating and talking as if an unexpected guest was an everyday occurrence. Fred was in good spirits, bestowing on me a mysterious knowing wink inbetween mouthfuls of food.’

‘Tashy’ and ‘Knock-Knock’

‘I had never before seen him without a raincoat and trilby and I was about to enquire if he, like me, had been dragged in for lunch, when suddenly, in the open door facing me, appeared two very large men. Both were clad in dirty oil-stained boiler suits and wore bicycle clips. I felt a sudden jolt of recognition which I tried to conceal. What were they doing dressed like this? I asked myself, as I confirmed that they were two usually smartly uniformed local constables, who languished under the nicknames of ‘Tashy’ and ‘Knock-Knock’.

‘Knock-Knock’, so called from his habit of knocking on walls with his truncheon, gaped in disbelief as he beheld Fred, who with every sign of enjoyment, was obviously employed in finishing a plateful of hash, using a large crust of bread to mop up the gravy. The constable pointed an accusing finger at him and gasped, ‘Ar saw you teckin bets at bottom o’ entry a minute since!’ ‘Nay, nay!’ cried the lady, whom I took to be our hostess, ”E’s bin ‘ere a gud hafe ‘our. Sithee, ‘ee’s nearly finished ‘is dinner an’ ar gerrim a reight dollop.’

‘Tashy’, whose large hairy appendage under his nose had labelled him with his moniker, glared at me and snapped, ‘Ooa you?’ I sat, petrified, fear depriving me of speech, but the lady’s husband quickly answered, ”E works at Viner’s, a pal o’ mine from theer sent ‘im on wi’ a jar o’ red cabbage.’ Fortunately, on the table stood the irrefutable evidence, and I marvelled at the quick-wittedness of my table companion.’

Relief!

‘After a cautionary look outside, satisfying myself that the coast was clear, I resumed my errand to James Bros, left the steel blocks, picked up a pair of machined dies and returned whence I came. A little bow-legged man lurked at the bottom of the bookie’s entry, stuffing betting slips and money into his pockets. He stopped me and muttered, ‘Ar’m standin’ in fer Fred ’til things cool darn. When thar brings bets temorra, gie ’em ter me, awright?’ When I got back to the factory, I related to Mac the story of my betting run. I was still full of admiration for the ingenuity of Bath Street people.’

PP. 110-112, Chapter 23, More George! (courtesy of The Hallamshire Press Limited).

No Comments

Add a comment about this page